The whole language movement emerged in the latter half of the 20th century as a response to the perceived limitations of phonics-based instruction. Grounded in the belief that learning to read is a natural process closely tied to meaning-making, whole language approaches emphasize the use of authentic texts, student choice, and reading and writing for real purposes.

People within the Movement

Central to the movement were researchers and educators such as Ken Goodman, Frank Smith, and Yetta Goodman. Ken Goodman famously described reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game,” arguing that readers use a combination of cues—semantic, syntactic, and graphophonic—to make sense of text. His work challenged the view that reading is a linear process of decoding letters and sounds. One of his influential works is What’s Whole in Whole Language? (1986).

Frank Smith contributed significantly to understanding the role of prediction and meaning in reading. He argued that skilled readers rely more on their expectations and understanding of language and context than on decoding every word. Smith’s research helped shift the focus from isolated skills to the importance of immersion in language-rich environments. His notable books include Understanding Reading (1971) and Reading Without Nonsense (1973).

Yetta Goodman, a leading advocate for miscue analysis and early literacy, emphasized the value of observing children’s natural learning processes. Her work supported the idea that children construct knowledge through interaction with meaningful texts and through opportunities to write and express themselves.

Louise Rosenblatt introduced the transactional theory of reading, which emphasized the dynamic relationship between the reader and the text. She distinguished between efferent and aesthetic reading stances and argued that meaning is created through the reader’s experience. Her foundational book is Literature as Exploration (1938).

James Moffett brought a broad, humanistic perspective to literacy education, advocating for student voice and expressive writing. His work, especially in Teaching the Universe of Discourse (1968), emphasized the developmental progression of writing and the importance of integrating reading and writing instruction in meaningful contexts.

Donald Graves revolutionized writing instruction by demonstrating that even very young children have powerful stories to tell. Through his classroom research, he showed how children thrive when given time, ownership, and authentic reasons to write. His work laid the foundation for the writing workshop model, which became integral to whole language classrooms.

Carolyn Burke and Cathy Short, longtime collaborators with Jerome Harste, contributed significantly to the development of whole language theory through their research on early literacy and literature-based instruction. Together, they co-authored Language Stories and Literacy Lessons (1984), which provided practical strategies for creating rich, integrated language learning environments.

Jim Trelease, through The Read-Aloud Handbook (first published in 1979), championed the importance of reading aloud to children from an early age. His work highlighted how hearing rich, complex language—well beyond a child’s independent reading level—helps build vocabulary, comprehension, and a lifelong love of reading. Trelease’s accessible, parent-friendly approach complemented the whole language emphasis on immersion in authentic texts.

Alfie Kohn has been a prominent voice critiquing behaviorist models of learning and advocating for student-centered, intrinsic motivation. While not a whole language researcher per se, his work supports many of its foundational beliefs. His key books include Punished by Rewards (1993) and The Schools Our Children Deserve (1999).

Randy and Katherine Bomer have championed authentic literacy practices, student voice, and choice in reading and writing. Randy Bomer’s Time for Meaning (1995) is a significant contribution to writing workshop and whole language pedagogy.

Patrick Shannon is known for his work on critical literacy and social justice in education. He has consistently critiqued corporate and standardized approaches to reading. His key texts include Reading Against Democracy (1998) and Education, Inc. (2007).

Jerome Harste and Dorothy Watson have long been involved in whole language and early literacy research. They emphasized inquiry, meaning-making, and integrated literacy experiences. Harste co-authored Language Stories and Literacy Lessons with Short and Burke.

Brian Cambourne developed the Conditions of Learning theory, based on observational research on how children acquire literacy in natural settings. His influential article “Toward an Educationally Relevant Theory of Literacy Learning” (1988) outlines these conditions.

Marie Clay’s work in early literacy led to the development of Reading Recovery. She emphasized close observation of children’s reading behaviors and early intervention. Key publications include Becoming Literate: The Construction of Inner Control (1991) and An Observation Survey of Early Literacy Achievement (1993).

Sylvia Ashton-Warner created a unique approach to literacy education grounded in the lives and language of children, particularly indigenous students in New Zealand. Her book Teacher (1963) remains a powerful statement on teaching and learning.

Together, these educators influenced classroom practices that prioritize student agency, literature-based instruction, and the integration of reading, writing, speaking, and listening. While the whole language approach has been the subject of debate, especially during the so-called “reading wars,” its core principles continue to inform balanced literacy models and progressive education movements today.

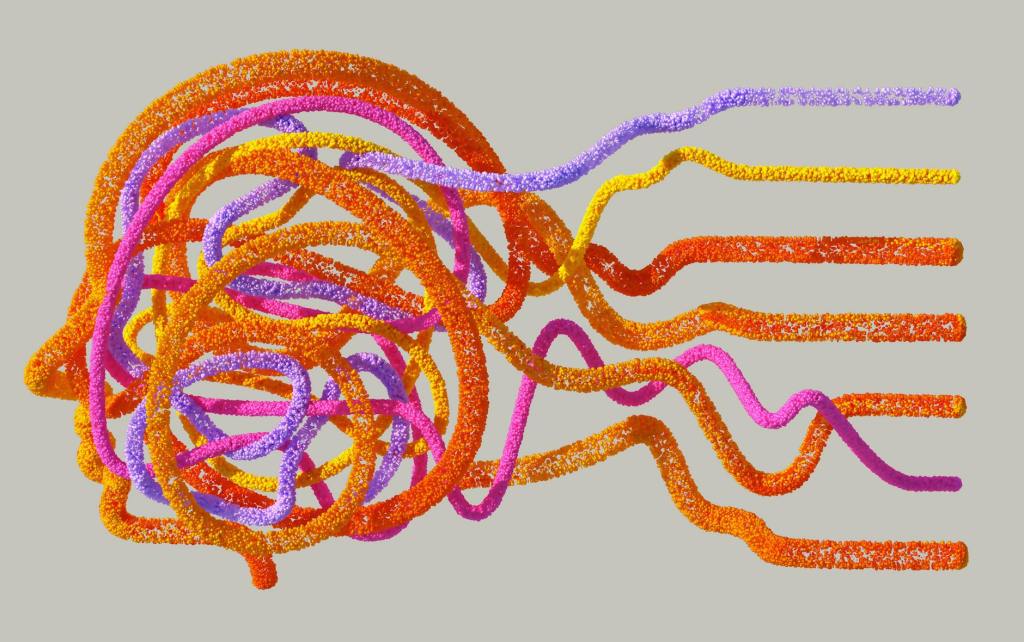

Three Cueing Systems: A Foundational Framework

One of the foundational frameworks used by whole language advocates—particularly in Marie Clay’s Reading Recovery program—is the Three Cueing Systems model. This model explains that readers rely on three types of information, or cues, to make meaning from text:

- Meaning (Semantic): Does the word make sense in the context?

- Structure (Syntactic): Does the word sound right grammatically?

- Visual (Graphophonic): Does the word look right based on the letters and sounds?

These cueing systems were used to analyze students’ reading behaviors in tools such as Running Records, allowing teachers to identify the strategies students use when reading and where they may need support. While some critics argue that this approach deemphasizes phonics, proponents emphasize that decoding is just one part of a much larger process aimed at understanding and making meaning from text.

What Happened to Whole Language?

Once standardized testing became the norm and phonics became the easiest way to “test” for reading skills, the basic premises of whole language came under strong criticism. Critics argued that whole language did not adequately address decoding, even though the approach emphasized comprehension—the very reason we read. Whole language supporters pointed out that focusing on isolated phonics skills, such as “spitting out vowel sounds,” does little to improve comprehension, which is the true measure of reading success.

Despite political pushback and policy shifts, the whole language movement’s influence continues to shape literacy education through balanced literacy models, reading and writing workshops, and integrated language arts instruction. More importantly, it continues to inspire educators who believe that reading and writing are acts of meaning-making—essential to democracy, agency, and joy.

References

- Ashton-Warner, S. (1963). Teacher. Simon & Schuster.

- Bomer, R. (1995). Time for meaning: Crafting literate lives in middle and high school. Heinemann.

- Cambourne, B. (1988). Toward an educationally relevant theory of literacy learning. The Reading Teacher, 41(8), 750–757.

- Cambourne, B. (1988). The whole story: Natural learning and the acquisition of literacy in the classroom. Ashton Scholastic.

- Clay, M. M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Heinemann.

- Clay, M. M. (1993). An observation survey of early literacy achievement. Heinemann.

- Goodman, K. S. (1986). What’s whole in whole language? Heinemann.

- Goodman, K. S. (1973). Miscue analysis: Applications to reading instruction. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Graves, D. H. (1983). Writing: Teachers and children at work. Heinemann.

- Graves, D. H. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Heinemann.

- Harste, J. C., Short, K. G., & Burke, C. L. (1984). Language stories and literacy lessons. Heinemann.

- Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton Mifflin.

- Kohn, A. (1999). The schools our children deserve: Moving beyond traditional classrooms and “tougher standards”. Houghton Mifflin.

- Moffett, J. (1968). Teaching the universe of discourse. Houghton Mifflin.

- Moffett, J. (1992). Active voice: A writing program across the curriculum. Heinemann.

- Rosenblatt, L. M. (1938/1995). Literature as exploration (5th ed.). Modern Language Association.

- Rosenblatt, L. M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Smith, F. (1971). Understanding reading: A psycholinguistic analysis of reading and learning to read. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Smith, F. (1973). Reading without nonsense. Teachers College Press.

- Shannon, P. (1998). Reading against democracy: The broken promises of reading instruction. Heinemann.

- Shannon, P. (2007). Education, inc.: Turning learning into a business. Routledge.

- Trelease, J. (1982/2013). The read-aloud handbook (7th ed.). Penguin Books.

- Watson, D. J. (1994). Whole language: Why bother? Heinemann.

Leave a comment